Bayou Bartholomew, the world’s longest stream, courses and curves for 359 miles through the Delta Lowlands of Arkansas and into northern Louisiana. This glorious stream formed some 1,800 to 2,200 years ago as the Arkansas River meandered through the soft soil of the floodplains of southeast Arkansas. The ever-curving meanders left a channel seemingly designed by 16th century French tailors; its many adjacent oxbow bend brakes and nearby lakes, formed as time wore on, hang like tattered pieces of a once fully-sewn ruff.

Bayou Bartholomew starts northwest of Pine Bluff, Arkansas, near the river’s change from a southward stretch (from Little Rock to Pine Bluff) to a more eastward direction. From Pine Bluff, Bayou Bartholomew curves through the Delta Lowlands, with a sum-total south-southeast trajectory, running between Highway 425 and Highway 65, until it ends near Sterlington, Louisiana. The Sterlington area is where the bayou joins the Ouachita River.

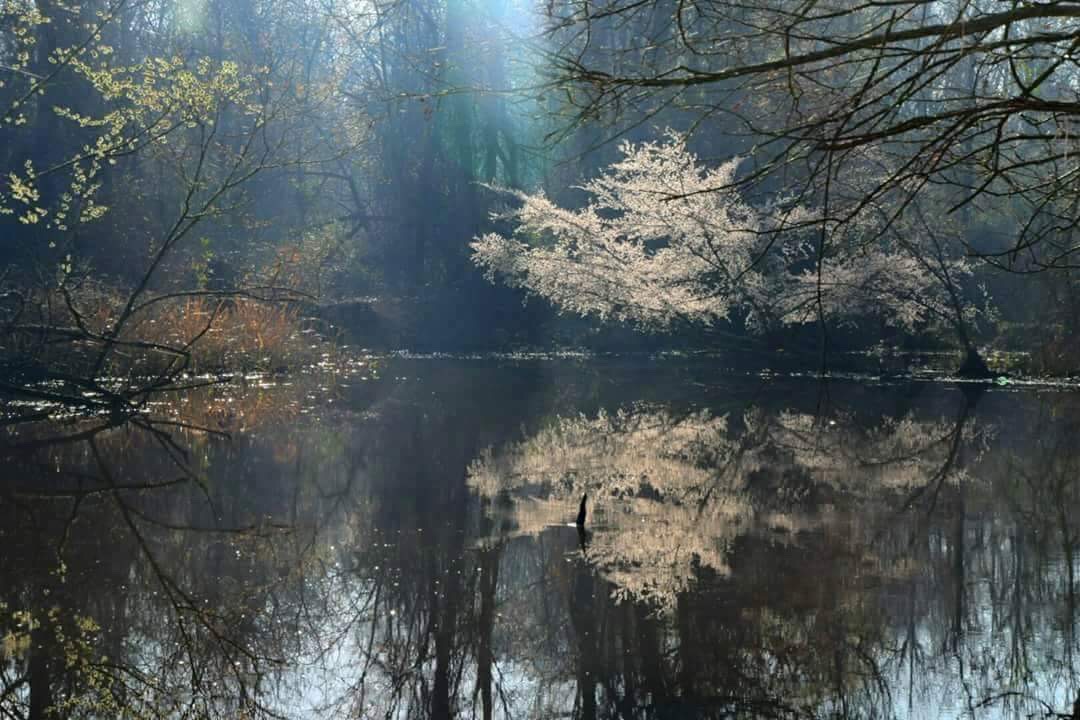

Along the way, habitats for 117 species of fish, 197 species of birds, and more than 50 species of mussels can be found, making it one of the most diverse streams in North America. Cypress and tupelo trees along with alligators, basking turtles, waterfowl, and songbirds make their homes here. The biodiversity is thought to have flourished due to the lack of river engineering; the bayou escaped being dammed, even.

Bayou Bartholomew and U.S. History

The term bayou was used by French settlers of the lower Mississippi River area. It is derived from the Choctaw (Muskogean language) term for creek or river: bayuk (or bayok). The Louisiana French adaptation became bayouque before being shortened to bayou in the mid to late 18th century. The current usage of the term bayou means stream, channel, minor river, or body that drains wetlands. The name Bartholomew came from the French Catholic settlers, whether as homage to Saint Bartholomew or simply from a French surname.

Historically, Bayou Bartholomew has served as a transportation route for centuries. While some peoples are not documented, the Quapaw are well known to have lived in the area and to have navigated Bayou Bartholomew. Later, in the 19th century, they would hide in and around Bayou Bartholomew as they were forced from their homeland and sometimes resisted leaving.

Slaves, too, ran to the bayou to hide from cruel slave owners. This stream was a place of refuge, of sorts, though one can only imagine the water snakes, alligators, and other wildlife encountered.

As settlers of French and other European patrilineage settled into the area, especially after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the bayou became a main route for steam boat travel into an otherwise landlocked area. This contributed significantly to the timber and agricultural industries of southern and central Arkansas until the Civil War. During the war, however, the bayou was allowed only for steamboats carrying troops and supplies, particularly by confederates.

In 1865, however, Union cavalry, led by Colonel Embury D. Osband, captured a confederate steamboat, used it to transport union troops across Bayou Bartholomew , and then burned the boat. This event’s significance cannot be overstated. Though other areas of Arkansas were largely under Union control by late 1863, with reconstruction in progress, southern and southeast Arkansas, like northern Louisiana, were still dominated by confederate soldiers. But the Union army’s capture of the steamboat meant Union control of this significant stretch of Bayou Bartholomew. And control of Bayou Bartholomew meant a shift in control of the region and the war’s outcome.

After the war, the steamboats once again used the Bayou to ship cotton, primarily, until railroad lines were constructed in the area around 1890. Across the eras, the bayou defined social and cultural history in recreation and worship, too. People swam and fished in the stream and held picnics nearby. Baptisms in the bayou were quite common and drew large gatherings, even by descendants of slaves who had once sought temporary refuge among the bayou’s cypress trees and wildlife.

Bayou Bartholomew in Recent Times

In the twentieth century, industrial and other pollution took a toll on Bayou Bartholomew. A lack of environmental awareness combined with new opportunities for recreation allowed the decline to happen at a faster pace. Also, urban development cleared too many trees from the banks and thus caused bank erosion; it also increased temperatures and, ultimately, stress on the aquatic life. The problem was more pronounced and lasted over a longer period in Arkansas, as Louisiana’s portion is protected under the Louisiana Natural and Scenic Rivers System created in 1970.

In 1995, Dr. Curtis Merrell of Monticello, Arkansas, organized the Bayou Bartholomew Alliance to restore and preserve the bayou. Dr. Curtis and Dr. William “Bill” Layher led the Alliance and, over time, an increasing number of conservation-minded volunteers in the clean-up of Bayou Bartholomew. The Alliance also educated the public about its historic and ecological importance. As their efforts grew and plans refined, the Alliance received numerous state and federal grants to devote to the bayou’s conservation; the group also earned the Forest Conservationist of the Year in 2000 from the Arkansas Wildlfe Federation, a nonprofit that advocates for sustainable use of wildlife habitats and natural resources. After Dr. Merrell’s passing in 2014, Dr. Layher continued the mission and earned his own well-deserved Water Conservation Award; the world lost this fine conservationist also just this year.

Today, thanks to the Bayou Bartholomew Alliance, Dr. Merrell, Dr. Layher, and Louisiana’s conservation system, people enjoy Bayou Bartholomew for its scenic view and for water sports, particularly canoeing and kayaking. The unengineered stream allows more natural paddling and awe-inspiring views of nature. Access points can be found in or near Pine Bluff, Star City, and Boydell in Arkansas and near Bastrop in Louisiana.